THE 2 PRINCIPLES

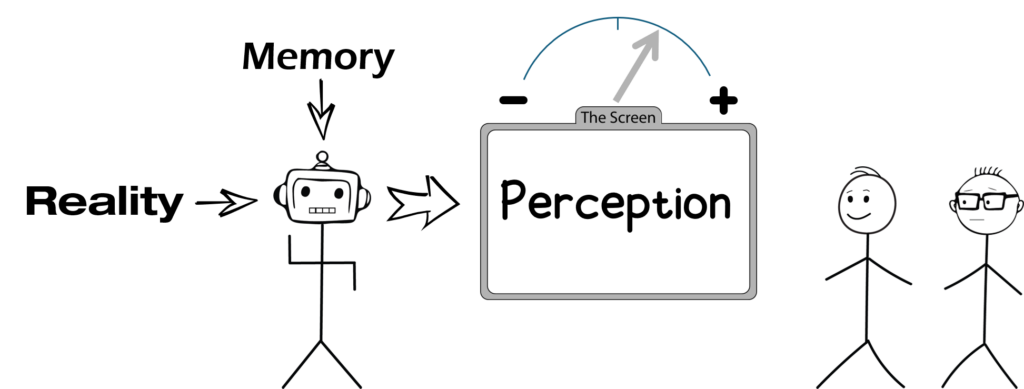

Perception IS NOT Reality

What we see isn’t always the truth—it’s shaped by our experiences, emotions, and biases. Two people can experience the same event differently because perception is personal, not objective.

- Our brains filter reality based on past experiences (called The Robot.)

- Emotions shape what we see—stress makes challenges feel bigger, confidence makes them feel smaller (Emotion as a Driver.

- Cognitive biases distort truth—we notice what we expect, not always what’s real.

When we recognize that our perception isn’t the full picture, we make better decisions, communicate more effectively, and react with more clarity.

Before reacting, ask: “Is this reality, or just my interpretation?”

Tell Me More

“Perception is not reality” means that the way we interpret the world is shaped by our experiences, biases, and emotions—not necessarily by objective truth. While we often believe we see things “as they are,” in reality, we see things as we are.

Key Ideas Behind This Concept

- Our Brains Filter Information: We don’t take in all available information—we filter it based on past experiences, expectations, and cognitive biases.

- Two People Can See the Same Situation Differently: A manager giving feedback may think they’re helping, but an employee might perceive it as criticism. Neither is wrong—but their interpretations are shaped by their perspectives.

- Emotions Influence Perception: When we’re stressed, challenges feel overwhelming. When we’re confident, those same challenges feel like opportunities. The situation hasn’t changed—just our perception of it.

- Cognitive Biases Distort Reality: The confirmation bias makes us seek information that supports our beliefs, while the negativity bias makes us focus on problems more than positives—both shape what we see as “true.” There are over 200 know cognitive biases.

Why This Matters in Work & Life

Better Decision-Making: Recognizing that perception isn’t always reality helps us pause before reacting.

Stronger Relationships: Understanding that others see things differently improves communication and reduces conflict.

More Resilience: When we realize our frustration or anxiety is partly shaped by perception, we can shift our thinking and respond more effectively.

A Practical Takeaway

Before reacting to a situation, ask:

“Is this the full truth, or just my interpretation of it?”

Challenging our perceptions helps us make clearer, more effective choices.

All Decisions Are Emotional

Every decision we make—big or small—is influenced by emotion, even when we think we’re being purely logical. Our brain processes decisions through both logic (reasoning) and emotion (feelings, instincts, biases), but emotions often tip the scales when making a choice.

- Logic provides options. Emotion drives action.

- Even “rational” decisions feel right or wrong.

- Without emotion, decision-making is impossible. (Studies on brain-damaged patients show they struggle to make choices when emotions are impaired.)

We may justify choices with logic, but emotion makes us decide.

Tell Me More

We like to think we make rational, logical decisions, but in reality, emotion is always present in the process. Research in neuroscience and psychology confirms that even our most “rational” decisions involve emotions at a core level.

Why? The Brain’s Decision-Making System

- Logic vs. Emotion: The prefrontal cortex (logic) and limbic system (emotion) work together. Logic analyzes choices, but emotion provides motivation and urgency.

- Without Emotion, We Can’t Choose: Neurologist Antonio Damasio’s research found that patients with damage to emotion-processing areas of the brain could analyze pros and cons endlessly but couldn’t make a final decision.

- Emotions Create Meaning: Facts alone don’t drive action—how we feel about those facts does. This is why marketing, leadership, and personal decisions all rely on emotional triggers.

Real-World Examples of Emotional Decisions

Buying a car? You justify it with fuel efficiency and price—but the final choice is based on how the car makes you feel.

Hiring an employee? Resumes show skills, but gut instinct and personal connection influence the final choice.

Major life changes? We analyze pros and cons, but our feelings about risk, reward, and identity make the final call.

Takeaway: Recognizing Emotion in Decisions Leads to Better Choices

Instead of pretending to be “purely logical,” successful leaders and decision-makers acknowledge emotions and use them wisely.

Ask yourself: “What’s driving this choice—fear, excitement, confidence?”

Balance logic and feeling to make more aligned, intentional decisions.

“We justify decisions with logic, but emotion makes them happen.”

THE 3 DRIVERS

The Robot

Overview

Tell Me More

The Robot is our autopilot system—it controls habits, reactions, and unconscious behaviors. It helps us navigate daily life without constantly thinking about every small decision. The Robot is essential for efficiency, but it doesn’t question itself—it simply repeats what it knows.

- The Good: It saves energy, helps us react quickly, and automates behaviors so we don’t have to consciously decide everything.

- The Challenge: It doesn’t distinguish between helpful and harmful patterns—it will repeat old habits, biases, and emotional reactions unless we interrupt it with awareness.

When we let The Robot run unchecked, we get stuck in patterns that limit growth, creativity, and intentional decision-making.

But when we recognize its role, we can break free from automatic responses and take more control over our actions.

Roles

The Screen

Our Internal Perception in the Moment

What It Does: The Robot filters how we experience reality. Every situation we encounter is translated by the Robot and then displayed on The Screen, which is shaped by past experiences, biases, and expectations. Our logic and emotion is then based on that perception, not on reality.

How It Affects Us: We don’t see the world as it is—we see it through The Screen. If The Screen is cloudy with stress, fear, or assumptions, our reactions will be distorted.

Example: You get a short email from your boss. If your Screen is shaped by insecurity, you assume they’re upset with you. If your Screen is clear, you just see it as a neutral message.

Autopilot

Our Habitual Reactions & Default Mode

What It Does: The Robot keeps us running on default behaviors, reactions, and thinking patterns. These are things we do without thinking—some helpful (brushing your teeth), some limiting (defensive reactions in conversations).

How It Affects Us: When The Robot is in control, we’re reacting, not thinking. This can make us repeat unhelpful habits, fall into negativity loops, or resist new ways of thinking.

Example: Someone gives you feedback, and you automatically defend yourself instead of considering it. That’s Autopilot taking over.

The Comfort Zone

Sticking to What Feels Safe & Familiar

What It Does: The Robot prefers what’s known over growth. It keeps us in familiar situations—even when they’re not good for us—because staying the same feels safer than change.

How It Affects Us: It makes us resist new challenges, avoid discomfort, and fear failure. Breaking out of The Comfort Zone requires overriding The Robot and engaging Logic and Emotion to reprogram the Robot.

Example: You hesitate to speak up in a meeting, even though you have a great idea. The Robot sees it as a risk, so it keeps you quiet to avoid discomfort.

Emotion

Overview

“Many psychological scientists now assume that emotions are the dominant driver of most meaningful decisions in life. Put succinctly, emotion and decision making go hand in hand.” – Annual Review of Psychology

Emotion is the driving force behind motivation, meaning, and connection. It helps us create, protect, and respond to the world—but it can also hijack our decisions if left unchecked.

Tell Me More

Emotion is our source of energy, purpose, and instinctive reactions. It fuels our creativity, relationships, and motivation to act. Without it, we wouldn’t care about anything. But emotions aren’t just about joy and excitement—they also include fear, anger, and frustration.

- The Good: Emotion gives meaning to our work, relationships, and goals. It fuels passion, creativity, and deep connection.

- The Challenge: Emotion can override logic, causing impulsive reactions, misinterpretations, and irrational fears.

Emotion plays two primary roles: Create and Protect. When we feel safe, Emotion helps us create. When we feel threatened, Emotion switches to protection mode—often triggering automatic reactions.

Tell Me More

The Robot is our autopilot system—it controls habits, reactions, and unconscious behaviors. It helps us navigate daily life without constantly thinking about every small decision. The Robot is essential for efficiency, but it doesn’t question itself—it simply repeats what it knows.

- The Good: It saves energy, helps us react quickly, and automates behaviors so we don’t have to consciously decide everything.

- The Challenge: It doesn’t distinguish between helpful and harmful patterns—it will repeat old habits, biases, and emotional reactions unless we interrupt it with awareness.

When we let The Robot run unchecked, we get stuck in patterns that limit growth, creativity, and intentional decision-making.

But when we recognize its role, we can break free from automatic responses and take more control over our actions.

Roles

Create

The Energy and Fuel that drives Decisions and Experience

- What It Does: When we feel safe and inspired, Emotion fuels creativity, connection, and personal growth. It’s what drives us to build new things, take risks, and find meaning in our work and relationships.

- How It Affects Us: In this mode, Emotion works for us, helping us take action, form deep bonds, and pursue meaningful goals.

Example: A musician lost in the moment of playing, an entrepreneur fueled by a vision, or a leader inspiring their team—all are powered by Emotion in Create mode.

Triggering

What Switches Us Into Protection Mode

- What It Does: A trigger is any external event or internal thought that Emotion interprets as a threat. It can be a tone of voice, a bad memory, an insecurity, or an unexpected challenge.

- How It Affects Us: Triggers active Protect Mode and can stimulate old emotional responses, often causing overreactions or emotional shutdowns. Recognizing triggers is key to regaining control.

Example: A simple question like “Why did you do it that way?” might trigger someone who has a history of feeling criticized, making them react defensively even if no harm was intended.

Getting triggered is how we put other people in charge of our lives.

Protect

Defending Against Perceived Threats

- What It Does: When we perceive a threat—real or imagined—Emotion shifts from creating to protecting. This triggers defensive reactions like fear, anger, or shutting down.

- How It Affects Us: Emotion in Protect mode makes it harder to use Active logic, pushing us toward fight, flight, freeze, or fawn responses instead of rational choices.

Example: If someone challenges your idea in a meeting and you instantly feel defensive or embarrassed, that’s Emotion shifting to Protect mode.

Logic

Overview

- Override Mode is effortful but necessary for growth.

- Active Mode is efficient but can be misleading.

- Idle Mode is necessary for recovery and creativity.

Tell Me More

Logic processes information, evaluates decisions, and creates narratives to explain our experiences. However, Logic operates in three modes:

- Override Mode is effortful but necessary for growth—it helps us challenge assumptions, make better decisions, and refine our understanding.

- Active Mode is efficient but can be misleading—it keeps us functioning day-to-day but is prone to bias and emotional influence.

- Idle Mode is necessary for recovery and creativity—when used intentionally, it prevents burnout and enhances well-being.

Roles

Override

This is the highest level of logical engagement—when we step outside our default decision-making machine and think about thinking. In this state, we question assumptions, challenge biases, and analyze our thought processes objectively.

- Perception is NOT reality—we challenge what we see, hear, and feel. We are curious and even suspicious of the screen.

- Emotions are examined, not obeyed—we question how we feel, where the emotion came from, and whether it fits the present situation.

- Logic is under review—we actively look for flaws, errors, and biases in our reasoning.

Tell Me More

Example: You receive an email from your manager with a vague, critical comment about your recent project. Your initial reaction is frustration.

- Instead of reacting immediately, you pause and analyze:

- “Why am I feeling defensive? Is this email actually as bad as it seems, or am I interpreting it negatively?”

- “What assumptions am I making about their intent?”

- “Is there another way to read this email that isn’t negative?”

- You decide to clarify the manager’s intent before responding emotionally.

✅ Key takeaway: You are stepping outside of your immediate reaction, questioning your emotions and thought process, and intentionally adjusting your perspective before making a decision.

Active

This is where most day-to-day thinking happens. Logic still operates, but it isn’t questioning itself—it’s working in service of perception and emotion.

- Perception IS reality—we take our interpretation of the moment as truth without questioning it.

- Emotion is the dominant driver—we assume our feelings are entirely caused by the present situation.

- Logic works to justify, not challenge—we unconsciously engage in confirmation bias, cherry-picking information to validate the screen and our emotional state.

Tell Me More

Example: You receive the same vague, critical email from your manager.

- Without thinking, you assume:

- “They don’t appreciate my work.”

- “They always criticize me.”

- “This is unfair.”

- Your logic isn’t questioning the situation—it’s reinforcing how you feel.

- You immediately reply defensively: “I don’t think that’s a fair criticism. I did exactly what was asked.”

- Later, you realize you misunderstood their intent.

❌ Key takeaway: You accepted your emotional response as truth without questioning it. Your logic worked to justify your feelings rather than assess the situation objectively.

Idle

Idle mode isn’t inherently bad—it’s essential. This is when logic disengages from active analysis for rest, recreation, or avoidance.

- We don’t want to think critically—our brain takes a break from analyzing and problem-solving.

- Often aided by external influences—we might use TV, movies, music, or even substances to help us “turn off” active thought.

- Can be positive (Flow State)—in some cases, Idle mode allows us to focus intensely on an activity without distraction from past or future concerns.

Tell Me More

Example: After a long day of work, you sit on the couch and turn on Netflix.

- You aren’t analyzing anything critically.

- Your brain isn’t actively working through problems—it’s just absorbing entertainment.

- If someone asked you to solve a work-related problem, you’d probably resist:

- “I don’t want to think about that right now.”

- Positive Idle Example: If you’re in a Flow State, you might be completely engaged in a hobby (painting, playing music, sports) where your logic isn’t actively questioning—it’s just doing.

✅ Key takeaway: Idle Mode isn’t bad—it’s necessary for rest and recovery. It can also be productive (e.g., flow states), but it’s not where deep thinking or analysis happens.

THE 4 SKILLS

Purposeful

Overview

Juggling Three Equally Important Elements

Being Purposeful means balancing three key areas:

- Purpose → What and Why

- Plan → How and When

- Present → Measures and Monuments

Thought Process

Purpose

What and Why

What uses Logic. Tangible and specific targets in the future.

Why uses Emotion: What will it feel like along the way and when you are there? What is your fuel source?

Tell Me More

WHAT

Tangible things are the “what” you create, often expressed as goals. Goals are engaging until achieved, but without a meaningful “why,” they lose their power.

These need to be specific, identifiable, and measurable.

WHY

Intangible experiences are the “why” behind creation—things like feeling accomplished, making a difference, or contributing to a better world. Of the six elements of being purposeful, this is the area where most people struggle.

Pleasures vs. Gratifications:

Pleasures engage the senses and emotions. They are short-lived and easy to access, such as eating, watching a movie, or scrolling social media.

Gratifications, on the other hand, fulfill higher needs—cognitive, aesthetic, or self-actualization. They require long-term effort and bring a sense of wholeness, like parenting, creating art, or playing sports.

Assessments:

To help clarify your “why” and identify what is truly gratifying for you, we recommend two assessments:

– The VIA Character Strengths Survey (Free to $49)

– The SDI ($140)

Concepts:

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) provides a framework for understanding your “why” by identifying what truly motivates you. It highlights three core psychological needs that drive deep purpose:

- Autonomy – The need for control over choices.

- Competence – The desire to feel capable and effective.

- Relatedness – The importance of feeling connected and making an impact.

When all three needs are met, people experience genuine purpose and motivation, making SDT a valuable tool for discovering a meaningful “why.”

Finally, remember the Happiness Formula:

Happiness = Reality – Expectations.

Plan

How and When

How is the specific steps to take along the way. This should include Milestones that break things down into steps that use the Flow guide of +4% for the level of challenge.

When uses logic for the timeline, and emotion for the payoff along the way and in each step.

Tell Me More

Both How and When are Logic driven, and like all actions, they need an emotion/energy source. Use this as a guide to keep track of where you are sourcing your energy.

Four Categories of Engagement & Payoff:

- Bad Now / Bad Later → This engagement should be avoided. It includes bad habits or actions driven by despair and apathy, where neither the present nor the future benefits.

- Good Now / Bad Later → In moderation, this can be fine—like splurging on a purchase or eating something unhealthy. These actions bring immediate pleasure but have negative long-term consequences. While we don’t need to be perfect, this category doesn’t provide a strong foundation for meaningful engagement.

- Bad Now / Good Later → The most common type of motivation, where we endure discomfort in the present for a future reward. This looks like exercising even when we don’t enjoy it or working late to build a career. This strategy is effective but can lead to burnout if overused.

- Good Now / Good Later → The ideal motivator—doing something enjoyable that also leads to long-term benefits. This includes loving your work, enjoying exercise, or engaging in fulfilling relationships. While harder to find, this category creates sustainable motivation and lasting engagement.

Understanding these categories helps you identify which type of motivation you’re relying on and whether you need to shift your energy source for a more fulfilling and sustainable path.

Present

Measures and Monuments

Measures use logic to define what progress looks like along the way.

Monuments are reminders of your purpose that keep you emotionally engaged, helping you stay focused and committed.

Tell Me More

“You can’t get there from not here.” If we move forward with an inaccurate understanding of our present reality, we will constantly face failure and frustration, leading to disengagement.

Sometimes, we deny reality because we don’t want to deal with it. Other times, we tell ourselves lies or half-truths to feel better about where we are. And in some cases, we simply don’t know the full truth yet.

It’s also important to recognize what is driving us in the present. When motivated by Protection, we engage with our goals out of fear or avoidance rather than inspiration.

This is where the Unbiased and Collaborative skills become valuable. They help us see the present more clearly and work with others to navigate challenges, ensuring we stay connected to our purpose in a meaningful way.

Resilient

Overview

Creation is the drive to bring what you value into the world.

Protection is the drive to restore or defend what you value.

We are triggered when we perceive danger and our ability to create is blocked or restricted.

Being Resilient is about being triggered less and recovering faster when we are.

Being triggered is how we put other people in charge of our lives.

Thought Process

Fix

Is this personal?

Understanding if something is personal helps us better interpret our reality. We often think things are about us when they are not.

When triggered, our focus shifts outward—blaming or fixating on the source of the trigger.

True resilience comes from taking control of your internal experience instead of letting external events dictate your emotions.

Most of the time, it’s not about you—people are focused on their own internal world and often have no idea how they affect others.

What are you protecting?

Asking, “What am I protecting?” is key to understanding what’s making you feel unsafe.

Being triggered is a fear state, but it’s often easier to identify what we feel is at risk rather than the fear itself.

If we felt completely safe, we wouldn’t be triggered.

The real source of the threat isn’t always obvious—it might be status, reputation, certainty, or belonging.

Once you identify the risk, it’s easier to decide how to restore safety and move forward.

What can you control?

Sometimes we get triggered because we are trying to control things outside of our control.

Triggers often come from fighting reality—wishing someone behaved differently, expecting control over unpredictable factors.

Shifting focus to what you can influence reduces stress and helps regain stability.

If you can’t control the situation, you CAN control your response to it.

How triggered are you?

The more triggered we are, the more protective and internally focused we become.

Understanding our level of being triggered helps us assess reality and regain balance.

- Level 1: I WANT to fix this. You’re triggered but still thinking about more than just yourself and the trigger. Focus is on the other person.

- Level 2: I NEED to fix this. Rational thinking is fading, and you are only focused on what triggered you.

- Level 3: I’m DESPERATE to fix this. Everything is a threat, and you’re only focused on yourself.

Recognizing where you are helps determine the best way to reset and move forward.

What do you need to feel safe?

If you feel safe, you aren’t triggered. Getting untriggered is about restoring that feeling.

What steps can you take to restore safety?

Our brain responds to perceived threats using Fight, Flight, Freeze, or Fawn.

Ask yourself: Which of these do I feel right now?

Common ways to restore safety:

- Calm Down: If things are chaotic, focus on lowering energy.

- Speed Up: If nothing is being done, act decisively.

- Figure Out: If things feel unclear, slow down and gather information.

Prevent

Strengthen Logic

We can reduce the chance of being triggered by strengthening how we think:

- Rest and exercise → A healthy brain handles stress better.

- Mindfulness/Self-Awareness → Observe yourself instead of reacting automatically.

- Build the Purposeful, Unbiased, and Collaborative skills → These all support resilience.

Debugging

The Robot holds onto conditioned responses that make us trigger-prone. Debugging removes unhelpful conditioning:

- Understand fear → There is no bear chasing you.

- Don’t take things personally → Most people act based on their experience, not you.

- Do a Safety Assessment → Is there an actual threat, or just a perceived one?

- Have a Plan → Know how you’ll respond to common triggers.

Spot

What’s Their Focus?

When people are triggered, their focus narrows to what feels like a threat.

Use the three levels to gauge how triggered they are:

- Level 1: Focused on you.

- Level 2: Focused on what triggered them.

- Level 3: Focused only on themselves.

Look for the 3 Energies

People express triggers in different ways. Learn how different triggering can look in different people.

- Calm Down: Withdrawn or Uncomfortable.

- Speed Up: Amped Up or Urgent.

- Figure Out: Distant or Interrogating.

Help

Give Them What They Need

- Work with, not at them.

- Don’t force solutions—match their energy and help them find their path to safety.

If they need to Calm Down: Be calm with them. Never say “Calm down”—it backfires.

If they need to Speed Up: Match their urgency but point energy toward solutions, not frustration.

If they need to Figure Out: Slow down, remove emotion, and help assess the situation objectively.

Unbiased

Overview

Bias stems from predetermined beliefs about the present (The Robot).

We can achieve unbiased thinking on a specific topic—for a short time—with support.

Bias leads to logical errors when we defend the familiar (Comfort Zone) or prioritize satisfying emotions.

Remaining unbiased requires significant mental energy.

Being unbiased means staying open to different or even competing information.

Thought Process

Are you curious?

We can’t see past our biases without a sense of curiosity.

Are you willing to learn something new or be wrong about something you believe?

Bias comes from predetermined beliefs about the present, but with help, we can be unbiased about a specific topic for a short period of time.

Tell Me More

| “Are you curious?” is an easier question to answer than “are you biased?”

It’s easier to identify when we feel curious and when we don’t. We can’t see past our biases without a genuine sense of curiosity. We must be aware of the difference between wanting to see what is, and looking for information that validates what we want to see. It’s difficult to see our bias, because we don’t think our bias is a bias. If you don’t feel curious, bias is in charge and your Robot will protect the Comfort Zone. Are you willing to learn something new or be wrong about something you believe? Being Unbiased starts with knowing that you are biased and being willing to challenge it. Are you being creative or protective? It is very difficult to challenge our bias when triggered into Protection mode. If you are triggered, it’s time to deploy the Resilient skill. |

What's at stake?

Being unbiased takes a lot of energy.

Use this question as a drive to be willing to change your beliefs or perceptions.

The stronger the bias, the higher the stakes have to be to override it.

Bias is stronger when the outcome matters to us. Understanding what’s at stake helps us recognize when emotions or personal interests might be clouding our judgment.

Tell Me More

We simply do not have the time or mental energy to constantly question our thinking.

The Robot usually drives, which means most of your thinking is based on bias, or past conditioning. We have to pick and choose when to spend our limited Logic energy.

Use this answer to determine how much time you will devote to this.

The more important a decision feels, the harder it is to stay unbiased. We naturally want things to go in our favor, and that desire can:

– Make us overlook contradictory evidence.

– Cause us to downplay risks.

– Lead us to rationalize decisions instead of analyzing them.

When facing an important decision, ask yourself:

- Am I resisting new information because I don’t like what it means?

- Am I being objective, or am I prioritizing a preferred outcome?

- What would I advise someone else to do in my position?

Recognizing what’s at stake allows you to step back and make a more informed choice.

What do you want to be true?

What do you want to see? What is your emotional state (Create or Protect?)

Are you hoping for confirmation of what you currently believe to be true?

Being unbiased requires being open to different or competing information.

Tell Me More

Bias is hard to see, but it is easier to identify what you want to be right about – which is bias.

We can then remember that we overvalue the things we want to be right about and prevent confirmation bias.

Confirmation bias often disguises itself as curiosity. We think we are looking for what’s true when we are actually looking to protect the familiar zone.

What will you base this decision on?

What sources are you basing your decision on?

Who are you basing your decision on?

Being unbiased requires challenging what is thought to be true and listening to diverse and/or expert sources.

Decisions should be based on clear, reliable criteria rather than emotions or assumptions. Defining your standards in advance helps minimize bias.

Tell Me More

| Deciding on what – and on whom – you will base your decision can help you be more unbiased.

How diverse are your sources? If 4 out of 5 experts agree on something, and you agree with the 5th, you must have strong evidence to support that decision. Is this based on facts or opinion? We often have to make decisions without having all the facts, but we should seek out as many facts as possible, and know the difference between what is known to be true and what is thought to be true. The Robot will try to default to familiar patterns. Emotion may push you toward a choice that feels good in the moment. Active Logic helps override these influences by focusing on facts, context, and long-term impact. Before finalizing a decision, challenge yourself: If I were explaining this choice to someone else, could I justify it with clear reasoning, or would I be relying on personal feelings and assumptions? |

Collaborative

Overview

Our understanding of the world is greatly limited.

Big challenges bring great complexity and a greater need to gather others’ perspectives.

Collaboration builds stronger relationships and buy-in as well.

“Great discoveries and improvements invariably involve the cooperation of many minds.” Alexander Graham Bell

Thought Process

Do you want to collaborate?

Do you truly want to see what you don’t currently see?

Do you have the time to invest right now?

Our understanding of the world is greatly limited; true collaboration is about borrowing someone else’s screen.

Tell Me More

Confirmation bias, or seeking out information that validates our current beliefs, can disguise itself as curiosity and collaboration. This can create the Illusion of Collusion.

Confirmation bias, or seeking out information that validates our current beliefs, can disguise itself as curiosity and collaboration. This can create the Illusion of Collusion.

Your Robot can perceive collaboration as a threat to the Familiar Zone and sound alarms to avoid it.

We may also be hesitant to deeply collaborate out of fear of looking like we don’t already know.

Collaboration can be a clever way to avoid making a decision or having others to share the blame with.

The benefits of collaboration are making better decisions and building stronger relationships and buy-in.

Who are the right people?

“Great discoveries and improvements invariably involve the cooperation of many minds.” – Alexander Graham Bell

Choosing to collaborate is important, but choosing who to collaborate with is just as important.

Tell Me More

When searching for the right people to collaborate with, it helps to ask yourself these questions:

– Who has a viewpoint different from mine?

– Am I choosing someone just because they agree with me?

– Will they tell me the truth?

– Have I built enough emotional capital to ask them?

– What are my blind spots, and who can see past them?

– What skills don’t I have?

When Meeting

The purpose of this meeting is to collect, compare, and contrast what different people have on their screens. It’s NOT about who’s right or wrong; it’s about understanding the different ways of seeing the situation.

- State your intention to listen, learn, and collect information – not necessarily decide.

- State your issue. The topic of discussion, without lots of detail. For example, “I want to exercise more,” or “I want a promotion.”

- What does their screen say? How does this look in their life? This is them sharing their own experience of your area. This IS NOT giving advice or talking about you.

- What does your screen say? Now that you’ve heard from others, what is your current thinking?

- Now, ask for advice. What do you think would work for me?

Listen, take notes, ask questions, and practice active listening. Manage debates to avoid putting ideas aside or making people feel unsafe offering their points of view.

Follow-up

Others invested their time and energy to help you, so show your appreciation by letting them know the outcome.

This prevents the Illusion of Inclusion and builds Emotional Capital.

It is also a good form of support to help you take the steps needed to achieve your goals.

is proudly powered by WordPress